While Gabrio Perabò lived in Varese between late XVII century and mid XVIII century, Perabò’s golden age started its decline. He had four sons: Pier Paolo [1], Felice, Giuseppe [2], and Francesco [3].

Upon his death, Pier Paolo, the eldest, gained the right of primogeniture of the largest share of the family possessions, and on this account he became the most representative figure of the lineage. In fact, he was the heir of a conspicuous estate patrimony as well as the guardian of an exceptionally patrician influence, which endured the political and social changes that shocked the old European continent throughout the last decade of the 1700. Furthermore, as he was still young, he entered the political scene, and in 1740 he was elected to the Council of the Leaders of Varese. He died on June 15, 1796.

With no direct descendants, Pier Paolo left his brothers the notable inheritance: buildings in the centre of Varese and farming fields in the county surrounding the town. A remarkable patrimonial asset, which was not easy to divide between the four heirs. Therefore, in 1797 a year after Pier Paolo’s death, Emanuele Pinciara, an appraiser from Milan, was given the hard job to sort it out. Although it was facilitated partially by the new Theresa cadastre, it was a meticulous job that included plot surveys and assessment of the countless holdings. The subsequent creation of four separate hereditary bases was even arduous, since the appraiser had to moderate the heirs’ vain desires, and balance the complex mechanism of compensations. [4]

However, such a patrimony was already deteriorated: firstly, due to the decline of farm and estate incomes, secondly, as a result of its dismemberment between direct and indirect heirs. Therefore, it had lost its influential power, which was the foundation of the political hegemony of the lineage in Varese in the previous centuries.

In mid XIX century, the Perabò city compound was delimited to a few decaying residences, which had been already leased out for years. That was the sole part of the Perabò estate patrimony that lived through within the Company of Saint Mary. Only a century before, their city properties spread from Saint Rocco’s church on the high road, to Saint Lawrence’s church next to the Hospital of the Poor, and from Saint John the Evangelist church in the Monastery of the Ursuline Virgins, to Saint Antonimo’s church in the convent by the same name.

Rev. Pasquale Perabò, who had become the owner of that block overlooking Piazzetta San Rocco, believed that it needed a renovation. The request was submitted to the Commission of Urban Decoration in Varese, in 1829 (August 17, 1929. license n. 391, Commission of Urban Decoration).

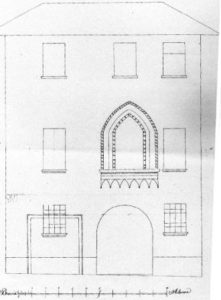

It was clear that the owner wanted to convert the upper storeys into habitable rooms, since the drawing of both the façades showed new rows of windows. Likewise, greater emphasis was given to the lancet window above the front gate.

1829. Renovation plan of both the West-facing and the East-facing façades of the Perabò Residence (plot 3042/1) before and after the remodelling works, which include windows (Municipal Archive of Varese).

Few years later, in 1832, since he wanted to embellish the appearance of the façade overlooking Piazzetta San Rocco, Rev. Pasquale Perabò submitted a request to the Commission of Urban Decoration for a construction permit. He wanted to create a new entryway next to the gate at the ground floor of the building in the former Via San Rocco (September 19, 1832. permit n. 1440 of September 20, 1832; permit n. 1446 of September 25, 1832 issued by the Commission of Urban Decoration of the Municipality of Varese).

1832. Renovation plan of the Perabò Residence (plot 3042/1) of the West-facing façade (Municipal Archive of Varese).

The aforesaid prelate was quite a singular figure. Since he was far away from his old family splendour, Don Pasquale usually worked hard everyday for the salary of a literature teacher at the School of Philosophy in Lodi, which allowed him to have at least a decent life.

As soon as the echo of the insurrectionary movements spread across Lombardy in 1848, Pasquale Perabò became one of its most passionate representatives. When he was appointed as a member of the interim government of Milan, he became a relevant character of those memorable days on the barricade. On this account, after he was purged and both his salary and teaching activities were suspended, he was pensioned off in 1854. [43] Back in Varese, he resumed his parish position as a confessor in both San Vittore’s Cathedral and in the church in Lower Biumo. Apparently, he died in financial straits at the Miogni’s on May 18, 1860. His death meant not only the extinction of the Perabò lineage in Varese, but the end of the old tradition of “the Perabò’s bread” as well.